READING PASSAGE 1

How to run a… Publisher and author David Harvey on what makes a good management book

A Prior to the Second World War, all the management books ever written could be comfortably stacked on a couple of shelves. Today, you would need a size able library, with plenty of room for expansion, to house them. The last few decades have seen the stream of new titles swell into a flood. In 1975, 771 business books were published. By 2000, the total for the year had risen to 3,203, and the trend continues.

B The growth in publishing activity has followed the rise and rise of management to the point where it constitutes a mini-industry in its own right. In the USA alone, the book market is worth over $1bn. Management consultancies, professional bodies and business schools were part of this new phenomenon, all sharing at least one common need: to get into print. Nor were they the only aspiring authors. Inside stories by and about business leaders balanced the more straight-laced textbooks by academics. How-to books by practising managers and business writers appeared on everything from making a presentation to developing a business strategy. With this upsurge in output, it is not really surprising that the quality is uneven.

C Few people are probably in a better position to evaluate the management canon than Carol Kennedy, a business journalist and author of Guide to the Management Gurus, an overview of the world’s most influential management thinkers and their works. She is also the books editor of The Director. Of course, it is normally the best of the bunch that are reviewed in the pages of The Director. But from time to time, Kennedy is moved to use The Director’s precious column inches to warn readers off certain books. Her recent review of The Leader’s Edge summed up her irritation with authors who over-promise and under-deliver. The banality of the treatment of core competencies for leaders, including the ‘competency of paying attention’, was a conceit too far in the context of a leaden text. ‘Somewhere in this book,’ she wrote, ‘there may be an idea worth reading and taking note of, but my own competency of paying attention ran out on page 31.’ Her opinion of a good proportion of the other books that never make it to the review pages is even more terse. ‘Unreadable’ is her verdict.

D Simon Caulkin, contributing editor of the Observer’s management page and former editor of Management Today, has formed a similar opinion. A lot is pretty depressing, unimpressive stuff.’ Caulkin is philosophical about the inevitability of finding so much dross. Business books, he says, ‘range from total drivel to the ambitious stuff. Although the confusing thing is that the really ambitious stuff can sometimes be drivel.’ Which leaves the question open as to why the subject of management is such a literary wasteland. There are some possible explanations.

E Despite the attempts of Frederick Taylor, the early twentieth-century founder of scientific management, to establish a solid, rule-based foundation for the practice, management has come to be seen as just as much an art as a science. Once psychologists like Abraham Maslow, behaviouralists and social anthropologists persuaded business to look at management from a human perspective, the topic became more multidimensional and complex. Add to that the requirement for management to reflect the changing demands of the times, the impact of information technology and other factors, and it is easy to understand why management is in a permanent state of confusion. There is a constant requirement for reinterpretation, innovation and creative thinking: Caulkin’s ambitious stuff. For their part, publishers continue to dream about finding the next big management idea, a topic given an airing in Kennedy’s book. The Next Big Idea.

F Indirectly, it tracks one of the phenomena of the past 20 years or so: the management blockbusters which work wonders for publishers’ profits and transform authors’ careers. Peters and Waterman’s In Search of Excellence: Lessons from America’s Best-Run Companies achieved spectacular success. So did Michael Hammer and James Champy’s book. Reengineering the Corporation: A Manifesto for Business Revolution. Yet the early euphoria with which such books are greeted tends to wear off as the basis for the claims starts to look less than solid. In the case of In Search of Excellence, it was the rapid reversal of fortunes that turned several of the exemplar companies into basket cases. For Hammer’s and Champy’s readers, disillusion dawned with the realisation that their slash-and-burn prescription for reviving corporate fortunes caused more problems than it solved.

G Yet one of the virtues of these books is that they could be understood. There is a whole class of management texts that fail this basic test. ‘Some management books are stuffed with jargon,’ says Kennedy. ‘Consultants are among the worst offenders.’ She believes there is a simple reason for this flight from plain English. ’They all use this jargon because they can’t think clearly. It disguises the paucity of thought.’

H By contrast, the management thinkers who have stood the test of time articulate their ideas in plain English. Peter Drucker, widely regarded as the doyen of management thinkers, has written a steady stream of influential books over half a century. ‘Drucker writes beautiful, dear prose.’ says Kennedy, ‘and his thoughts come through.’ He is among the handful of writers whose work, she believes, transcends the specific interests of the management community. Caulkin also agrees that Drucker reaches out to a wider readership. ‘What you get is a sense of the larger cultural background,’ he says. ‘That’s what you miss in so much management writing.’ Charles Handy, perhaps the most successful UK business writer to command an international audience, is another rare example of a writer with a message for the wider world.

Questions 1-2

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

1. What does the writer say about the increase in the number of management books published?

A It took the publishing industry by surprise.

B It is likely to continue.

C It has produced more profit than other areas of publishing.

D It could have been foreseen.

2. What does the writer say about the genre of management books?

A It includes some books that cover topics of little relevance to anyone.

B It contains a greater proportion of practical than theoretical books.

C All sorts of people have felt that they should be represented in it.

D The best books in the genre are written by business people.

Questions 3-7

Reading Passage 1 has eight paragraphs A-H. Which paragraph contains the following information!

3. reasons for the deserved success of some books

4. reasons why managers feel the need for advice

5. a belief that management books are highly likely to be very poor

6. a reference to books nor considered worth reviewing

7. an example of a group of people who write particularly poor books

Questions 8-13

Look at the statements (Questions 8-13) and the list of books below. Match each statement with the book it relates to.

8. It examines the success of books in the genre.

9. Statements made in it were later proved incorrect.

10. It tails to live up to claims made about it.

11. Advice given in it is seen to be actually harmful.

12. It examines the theories of those who have developed management thinking

13. It states die obvious in an unappealing way.

List of Books

A Guide to the Management Gurus

B The Leader’s Edge

C The Next Big Idea

D In Search of Excellence

E Reengineering the Corporation

READING PASSAGE 2

Stadium Australia

A You might ask, why be concerned about the architecture of a stadium? Surely, as Long as die action is entertaining and the building is safe and reasonably comfortable, why should the aesthetics matter’ This one question has dominated my professional life, and its answer is one 1 find myself continually rehearsing. If one accepts that sporting endeavour is as important an outlet for human expression as, say, the theatre or cinema, fine art or music, why shouldn’t the buildings in which we celebrate this outlet he as grand and as inspirational as those we would expect, and demand, in those other areas of cultural life? Indeed, one could argue that because stadiums are, in many instances, far more popular than theatres or art galleries, we should actually devote more, and nor less, attention to their form. Stadiums have frequently been referred to as ‘cathedrals’. Football has often been dubbed ‘the opera of the people’. What better way, therefore, to raise the general public’s awareness and appreciation of quality design than to offer them the very’ best buildings in the one area of life that seems to touch them most? Could it even be drat better stadiums might just make tor better citizens?

B But then maybe, as my detractors have labelled me in the past, 1 am a snob. Maybe I should just accept that sport, and its associated accoutrements and products, is an essentially tacky and ephemeral business, while stadium design is all too often driven by pragmatists and penny-pinchers. Certainly, when 1 first started writing about stadium architecture, one of the first and most uncomfortable truths 1 had to confront was that some of the mast popular stadiums in the world were also amongst the least attractive or innovative in architectural terms. ‘Worthy and predictable’ has usually won more votes than ’daring and different’. Old Trafford football ground in Manchester, the Yankee Stadium in New York, Ellis Park in Johannesburg. The list is long and is not intended to suggest that these are necessarily poor buildings. Rather, that each has derived its reputation more from the events that it has staged, from its associations, than from the actual form it takes. Equally, those stadiums whose forms have been revered – such as the Maracana in Rio, oi the San Siro in Milan – have turned out to be rather poorly designed in several respects, once one analyses them not as icons but as functioning ‘public assembly facilities’ (to use the current jargon). Finding the balance between beauty and practicality has never been easy.

C Homebush Bay was the site of the main Olympic Games complex for the Sydney Olympics of 2000. To put it politely, 1 am no great admirer of the Olympics as an event, or, rather, of the insane pressures its past bidding procedures have placed upon candidate cities. Nor, as a spectator, do 1 much enjoy the bloated Games programme and the consequent demands this places upon the designers of stadiums. Yet in my calmer moments it would be churlish to deny that, if approached sensibly and imaginatively, the opportunity to stage the Games can yield enormous benefits in the long term (as well they should, considering the expenditure involved), if not (or sport then at least for the cause of urban regeneration. Following in Barcelona’s footsteps, Sydney undoubtedly set about its urban regeneration in a wholly impressive way. To an outsider, the 760-hectare sire at Homebush Bay, once the home of an abattoir, a racecourse, a brickworks and light industrial units, seemed miles from anywhere – it was actually fifteen kilometres from the centre of Sydney and pretty much in the heart of the city’s extensive conurbation. Some £1.3 billion worth of construction and reclamation was commissioned, all of it, crucially, with an eye to post- Olympic usage- Strict guidelines, studiously monitored by Greenpeace, ensured that the 2000 Games would be the most environmentally friendly ever. What’s more, much of the work was good-looking, distinctive and lively. ‘That’s a reflection of the Australian spirit,’ I was told.

D At the centre of Homebush lay the main venue for the Olympics, Stadium Australia. It was funded by means of a BOOT (Budd, Own, Operate and Transfer) contract, which meant that the Stadium Australia consortium, led by the contractors Multiplex and the financiers Hambros, bore i he bulk of the construction costs, in return for which it was allowed to operate the facility for thirty years, and thus, it hopes, recoup its outlay, before handing the whole building over to the New South Wales government in the year 2030.

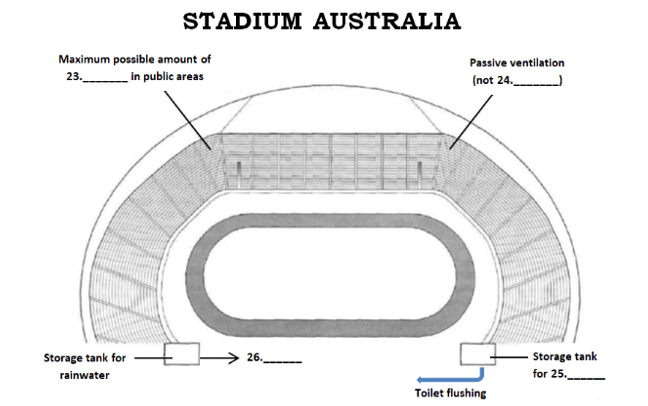

E Stadium Australia was the most environmentally friendly Olympic stadium ever built. Every single product and material used had to meet strict guidelines, even if it turned our to he more expensive. All the timber was either recycled or derived from renewable sources. In order to reduce energy’ costs, the design allowed for natural lighting in as many public areas as possible, supplemented by solar-powered units. Rainwater collected from the roof ran off into storage- ranks, where it could be tapped for pitch irrigation. Stormwater run-off was collected for toilet flushing. Wherever possible, passive ventilation was used instead of mechanical air- conditioning. Even the steel and concrete from the two end stands due to be demolished at the end of the Olympics was to be recycled. Furthermore, no private cars were allowed on the Homebush site. Instead, every spectator was to arrive by public transport, and quite right too. If ever there was a stadium to persuade a sceptic like myself that the Olympic Games do, after all, have a useful function in at least setting design and planning trends, this was the one. 1 was, and still am, I freely confess, quite knocked out by Stadium Australia.

Questions 14-18

Choose the correct heading for each paragraph from the list of headings below. Write the correct number i—x in boxes 14—18 on your answer sheet.

List of Headings

i A strange combination

ii An overall requirement

iii A controversial decision

iv A strong contrast

v A special set-up

vi A promising beginning

vii A shift in attitudes

viii A strongly held belief

ix A change of plan

x A simple choice

14. Paragraph A

15. Paragraph B

16. Paragraph C

17. Paragraph D

18. Paragraph E

Questions 19-22

In boxes 19-22 on your answer sheet unite

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN If there is no information on this

19. The public have been demanding a better quality of stadium design.

20. It is possible that stadium design has an effect on people’s behaviour in life in general.

21. Some stadiums have come in for a lot more criticism than others.

22. Designers of previous Olympic stadiums could easily have produced far better designs.

Question 23-26

Label the diagram below. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the reading passage for each answer. Write your answers in boxes 23-26 on your answer sheet.

READING PASSAGE 3

A Theory of Shopping

For a one-year period I attempted to conduct an ethnography of shopping on and around a street in North London. This was carried out in association with Alison Clarke. I say ‘attempted’ because, given the absence of community and the intensely private nature of London households, this could not be an ethnography in the conventional sense. Nevertheless, through conversation, being present in the home and accompanying householders during their shopping, I tried to reach an understanding of the nature of shopping through greater or lesser exposure to 76 households.

My part of the ethnography concentrated upon shopping itself. Alison Clarke has since been working with the same households, but focusing upon other forms of provisioning such as the use of catalogues (see Clarke 1997). We generally first met these households together, but most of the material that is used within this particular essay derived from my own subsequent fieldwork. Following the completion of this essay, and a study of some related shopping centres, we hope to write a more general ethnography of provisioning. This will also examine other issues, such as the nature of community and the implications for retail and for the wider political economy. None of this, however, forms part of the present essay, which is primarily concerned with establishing the cosmological foundations of shopping.

To state that a household has been included within the study is to gloss over a wide diversity of degrees of involvement. The minimum requirement is simply that a householder has agreed to be interviewed about their shopping, which would include the local shopping parade, shopping centres and supermarkets. At the other extreme are families that we have come to know well during the course of the year. Interaction would include formal interviews, and a less formal presence within their homes, usually with a cup of tea. It also meant accompanying them on one or several ‘events’, which might comprise shopping trips or participation in activities associated with the area of Clarke’s study, such as the meeting of a group supplying products for the home.

In analysing and writing up the experience of an ethnography of shopping in North London, I am led in two opposed directions. The tradition of anthropological relativism leads to an emphasis upon difference, and there are many ways in which shopping can help us elucidate differences. For example, there are differences in the experience of shopping based on gender, age, ethnicity and class. There are also differences based on the various genres of shopping experience, from a mall to a corner shop. By contrast, there is the tradition of anthropological generalisation about ‘peoples’ and comparative theory. This leads to the question as to whether there are any fundamental aspects of shopping which suggest a robust normativity that comes through the research and is not entirely dissipated by relativism. In this essay I want to emphasize the latter approach and argue that if not all, then most acts of shopping on this street exhibit a normative form which needs to be addressed. In the later discussion of the discourse of shopping I will defend the possibility that such a heterogenous group of households could be fairly represented by a series of homogenous cultural practices.

The theory that I will propose is certainly at odds with most of the literature on this topic. My premise, unlike that of most studies of consumption, whether they arise from economists, business studies or cultural studies, is that for most households in this street the act of shopping was hardly ever directed towards the person who was doing the shopping. Shopping is therefore not best understood as an individualistic or individualising act related to the subjectivity of the shopper. Rather, the act of buying goods is mainly directed at two forms of ‘otherness’. The first of these expresses a relationship between the shopper and a particular other individual such as a child or partner, either present in the household, desired or imagined. The second of these is a relationship to a more general goal which transcends any immediate utility and is best understood as cosmological in that it takes the form of neither subject nor object but of the values to which people wish to dedicate themselves.

It never occurred to me at any stage when carrying out the ethnography that I should consider the topic of sacrifice as relevant to this research. In no sense then could the ethnography be regarded as a testing of the ideas presented here. The Literature that seemed most relevant in the initial analysis of the London material was that on thrift discussed in chapter 3. The crucial element in opening up the potential of sacrifice for understanding shopping came through reading Bataiile. Bataille, however, was merely the catalyst, since I will argue that it is the classic works on sacrifice and, in particular, the foundation to its modern study by Hubert and Mauss (1964) that has become the primary grounds for my interpretation. It is important, however, when reading the following account to note that when I use the word ‘sacrifice’, I only rarely refer to the colloquial sense of the term as used in the concept of the ‘self-sacrificial’ housewife. Mostly the allusion is to this Literature on ancient sacrifice and the detailed analysis of the complex ritual sequence involved in traditional sacrifice. The metaphorical use of the term may have its place within the subsequent discussion but this is secondary to an argument at the level of structure.

Questions 27-29

Choose THREE letters A-F.

Which THREE of the following are problems the writer encountered when conducting his study?

A uncertainty as to what the focus of the study should be

B the difficulty of finding enough households to make the study worthwhile

C the diverse nature of the population of the area

D the reluctance of people to share information about their personal habits

E the fact that he was unable to study some people’s habits as much as others

F people dropping out of the study after initially agreeing to take part

Questions 30-37

Do the following statements agree with the views of the writer in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 30-37 on your answer sheet write

YES if the statement agrees with the views of the writer

NO if the statement contradicts the views of the writer

NOT GIVEN if it is impossible to say what the writer thinks about this

30. Anthropological relativism is more widely applied than anthropological generalisation.

31. Shopping lends itself to analysis based on anthropological relativism.

32. Generalisations about shopping are possible.

33. Tire conclusions drawn from this study will confirm some of the findings of other research.

34. Shopping should be regarded as a basically unselfish activity.

35. People sometimes analyse their own motives when they are shopping.

36. The actual goods bought are the primary concern in the activity of shopping.

37. It was possible to predict the outcome of the study before embarking on it.

Questions 38-40

Complete the sentences below with words taken from Reading Passage 3. Use NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS for each answer.

The subject of written research the writer first thought was directly connected with his study was (38)…………….

The research the writer has been most inspired by was carried out by (39)……………………

The writer mostly does not use the meaning of ‘sacrifice’ that he regards as (40)……………………

ANSWER