READING PASSAGE 1

The Spice of Life!

A When thinking of the most popular restaurant dish in the UK, the answer ‘chicken tikka masala’ does not spring readily to mind. But it is indeed the answer, often now referred to as a true ‘British national dish’. It may even have been invented by Indian immigrants in Scotland, who roasted chicken chunks (tikka), mixed them with spices and yoghurt, and served this in a bowl of masala sauce. The exact ingredients of the sauce vary from restaurant to restaurant, but the dish usually includes purced tomatoes and cream, coloured orange by turmeric and paprika. British cuisine? Yes, spices have come a long way.

B Spices are dried seeds, fruit, roots, bark, or vegetative parts of plants, added to food in small amounts to enhance flavour or colour. Herbs, in contrast, are only from the leaves, and only used for flavouring. Looking at the sources of some common spices, mustard and black pepper arc from seeds, cinnamon from bark, cloves from dried flower buds, ginger and turmeric from roots, while mace and saffron are from seed covers and stigma tips, respectively. In the face of such variety, it is becoming increasingly common for spices to be offered in pre-made combinations. Chili powder is a blend of chili peppers with other spices, often cumin, oregano, garlic powder, and salt. Mixed spice, which is often used in baking, is a British blend of sweet spices, with cinnamon being the dominant flavour. The ever-popular masala, as noted, could be anything, depending on the chef.

C Although human communities were using spices tens of thousands of years ago, the trade of this commodity only began about 2000 BC, around the Middle Last. Early uses were less connected with cooking, and more with such diverse functions as embalming, medicine, religion, and food preservation. Eventually, extensive overland trade routes, such as the Silk Road, were established, yet it was maritime advances into India and East Asia which led to the most dramatic growth in commercial activities. From then on, spices were the driving force of the world economy, commanding such high prices that it pitted nation against nation, and became the major impetus to exploration and conquest, It would be hard to underestimate the role spices have played in human history.

D Originally, Muslim traders dominated these routes, seeing spice-laden ships from the Orient crossing the Indian Ocean to Red Sea and Persian Gulf ports, from where camel caravans transported the goods overland. However, although slow to develop, European nations, using aggressive exploration and colonisation strategies, eventually came to rule the Far East and, consequently, control of the spice trade. At first, Portugal was the dominant power, but the British and Dutch eventually gained the upper hand, so that by the 19th century, the British controlled India, while the Dutch had the greater portion of the East Indies (Indonesia). Cloves, nutmeg, and pepper were some of the most valuable spices of the time.

E But why were spices always in such demand? There are many answers. In the early days, they were thought to have strong medicinal properties by balancing ‘humours’, or excesses of emotions in the blood. Other times they were thought to prevent maladies such as the plague, which often saw prices of recommended spices soar. But most obviously, spices flavoured the bland meat-based European cuisines. Pepper, historically, has always been in highest demand for this reason, and even today, peppercorns (dried black pepper kernels) remain, by monetary value, the most widely traded spice in the world. However, saffron, by being produced within the small saffron flower, has always been among the world’s most costly spice by weight, valued mostly for its vivid colour.

F Predictably, the majority of the world’s spices are produced in India, although specific spices arc often produced in greater amounts in other countries. Vietnam is the largest producer and exporter of pepper, meeting nearly one third of the world’s demand. Indonesia holds a clear lead in nutmeg production, Iran in saffron, and Sri Lanka in cinnamon. However, exportation of such spices is not always simple. Most are dried as a whole product, or dried and ground into powder, both forms allowing bulk purchase, easier storage and shipping, and a longer shelf life. For example, the rhizomes (underground stems) of turmeric are boiled lor several hours, then dried in ovens, after which they are ground into the yellow powder popular in South-Asian and Middle-Eastern cuisines.

G However, there are disadvantages in grinding spices. It increases their surface area many fold, accelerating the rate of evaporation and oxidation of their flavour-bearing and aromatic compounds. In contrast, whole dried spices retain these for much longer. Thus, seed-based varieties (which can be packaged and stored well) are often purchased in this form. This allows grinding to be done at the moment of cooking or eating, maximising the flavour and effect, a fact which often results in pepper ‘grinders’, instead of ‘shakers’, gracing the tables of the better restaurants around the world.

Questions 1-6

Reading Passage One has seven paragraphs, A-G. Choose the correct heading for Paragraphs B-G from the list of headings.

List of Headings

i Uses of spice

ii Spices for cooking

iii Changing leaders

iv A strange choice

v Preserving flavours

vi Famous spice routes

vii The power of spice

viii Some spices

ix Medicinal spices

x Spice providers

Example Answer Paragraph A iv

1. Paragraph B

2. Paragraph C

3. Paragraph D

4. Paragraph E

5. Paragraph F

6. Paragraph G

Questions 7-9

Complete the sentence. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Saffron, from the small (7)……………………of flowers, has a (8)……………………….and is mostly grown in (9)…………………..

Questions 10-13

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage One?

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN If there is no information on this

10. The ingredients of masala are fairly standardised.

11. The demand for spices led to greater exploration.

12. Vietnam consumes a lot of pepper.

13. Seed-based spices can be easily stored.

READING PASSAGE 2

Unsung and Lowly Creatures

Earthworms are not creatures likely to attract much attention. Socretive, silent, slow-moving, and featureless, almost no one would ever think. Let’s quote Charles Darwin, who wrote: ‘It may be doubted wheather there are many other animals whichs have played so important a part in the history of the world as have these lowly-organised creatures’.

That is high praise indeed for what is basically a slimy, muscular, moist, segmented tube. This tube is also hermaphroditic, meaning that there are both male and female segments in the one creature. Some segment contain testes, others eggs, released ooze, exchange, and store fluids, and then a long complicated process eventually leads to the secretion of an egg case. From this, small but fully-formed worms will emerge, reaching full size in about one year, and living for one or two years after that.

Yet earthworms are rarely seen, spending as they do their whole lives underground. Only after heavy rains can they sometimes be found on the surface, apparently stranded. Three hypotheses are put forward to explain this. The stormwater may flood their burrows, forcing them upwards. Alternatively, the worms may be taking advantage of the wet conditions to either travel more quickly through the open air (compared to burrowing beneath the ground), or otherwise to meet and mate. Whatever the case, if they find themselves on concreted, rocky, or hardened earth, they are effectively trapped. If this is during dawn, in high summer, or in the daytime, these earthworms quickly die due to bird predation or dehydration.

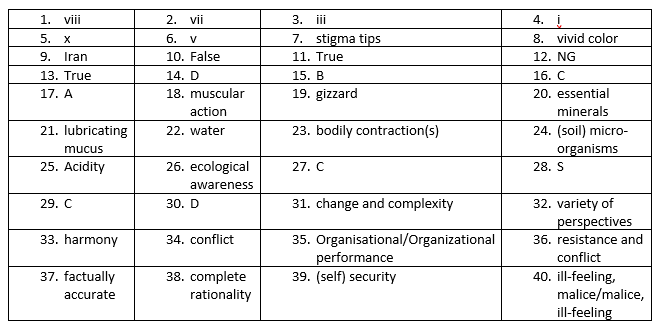

Normally, however, worms quietly go about their hidden business, and this often leads to an underestimation of their actual numbers. Darwin himself thought that arable land contained about 50,000 worms per acre, yet modern research has suggested that the figure could reach as high as almost two million. Putting this another way, the weight of earthworms beneath the soil is often greater than that of the cows, horses, and sheep are zing upon is surface. And those worms are just as hungry. Worms do, in fact, have a small mouth and a simple but effective digestive system, similar to the animals above, Food is sucked into the body, then pushed along the length of the worm through muscular action, passing through the crop, gizzard, intestine, and finally the anus.

Perhaps surprisingly, it is this constant eating which so benefits the chemistry of the soil. Earthworms feed on undecayed leaf litter and organic matter. They pull pieces down into their burrows, shred them into smaller parts, and then consume each of these, along with small soil particles. In the worms’ gut, everything is ground into a a fine paste, to be eventually excreted , releasing essential minerals in an easily accessible form. One single worm may produce over four kilograms of this digested paste per year. Multiply that by a million worms, and one can understand Darwin’s comment about ‘unsung creatures which, in their untold millions, transformed the land’.

The other great benefit relates to earthworms’ search for food. It might surprise many to know that these creatures are very mobile, moving to the surface then down into the safer depths on a daily basis. Aided by the secretion of lubricating mucus, they push themselves through the soil using waves of bodily contractions, which alternately shorten and lengthen their form. The point is, water can also move through their tunnels. More importantly, as the worms travel, they push air in and out of the soil on a continuous basis. In the same way that animals need oxygen, so too do the myriad micro-organisms in the soil. Thus, without worms, the ground would become waterlogged, airless, and less productive for farming purposes.

Naturally, with so many worms in the soil, they form the base of many food chains. Not only birds, but also some mammals, such as hedgehogs, moles, and even larger ones, such as foxes and bears, will actively dig into the ground of worms. Such predation is natural, and has little effect on worm populations. However, the use of certain fertilisers is a different case. Earthworms depend on the temperature, texture, and moisture content of the soil, but it is its acidity to which they are most sensitive. Nitrogenous fertilisers can raise this to levels fatal to these creatures, often causing disastrous drops in numbers. The more ecologically-aware farmer avoids such chemicals, and regularly adds a surface mulch of organic matter raising worm numbers for the natural benefit of both soil and man.

Questions 14-17

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

14. Charles Darwin thought that worms

A were only moderately important.

B were organised.

C liked arable land.

D numbered in the many millions.

15. A single worm

A is either male or female.

B has many segments.

C is a complicated organism.

D lives for about a year.

16. Stormwater may possibly

A clean out worm burrows.

B slow down worms.

C help worms encounter others.

D harden the earth.

17. Grazing animals

A often weigh less than the worms below.

B are hungrier than the worms below.

C have very different digestive systems from worms.

D have simpler digestive systems than worms.

Questions 18-24

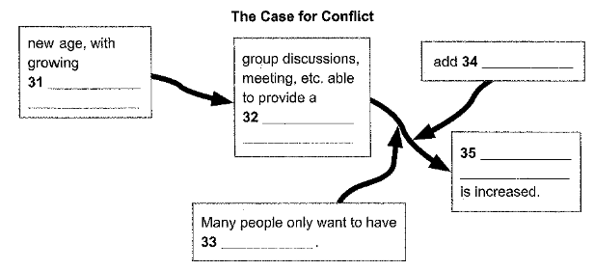

Complete the diagram. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Questions 25-26

Complete the sentences. Choose NO MORE THAN TWO WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Worm numbers will especially fall when the soil has high (25)………………..

Adding mulch to the soil shows (26)……………………..

READING PASSAGE 3

Organisational Conflict and Change

Change is a natural process. As humans, we are born, we grow, we mature, we decline, and we eventually die. On a bigger scale, modern existence is similarly in a constant state of flux, with global change, life strategic change, and personal change constantly upon us. With the current rate of technological advance, this is only happening at a faster pace. Putting it simply, life is change, and in a manner never before experienced.

Organisations, also, are analogous to organisms. They similarly grow, mature, suffer injury and crises, and may well die (for example, become bankrupt). The implications of this new ‘change paradigm’ are that the stable structures and static systems which in the past made organisations strong, now only contribute to their decline. Textbooks cite many examples of this: large monolithic institutions that failed to respond to external circumstances. Many were former government monopolies, and their break-up into smaller divisions was one attempt to deal with this issue. The message was clear: respond to change, or fail to thrive.

However, the big problem is that change promotes resistance among people. It brings a degree of discomfort, which in turns results in conflict. Thus, since change is constant, so too must be this conflict, and it is this which must be considered. The word ‘conflict’ has negative connotations, and deservedly so. It is often the result of negative forces, producing negative results. Resources are diverted, judgements distorted, co-ordination reduced, and ill-feeling generated. It thus seems strange to argue that conflict is not necessarily unwelcome, and can, in fact, be necessary, yet that is exactly what I propose.

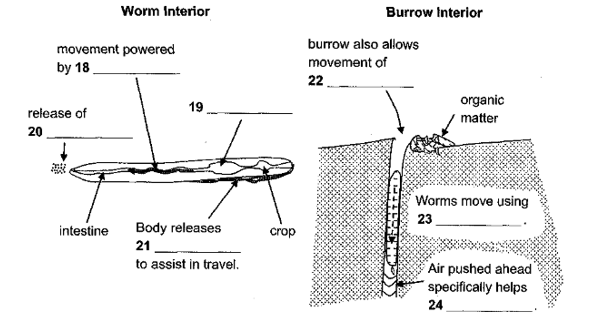

To understand this, we must first accept one crucial fact: in this new era of increasing change and complexity, accurate and considered decision-making is critical, and can no longer be considered the province of just one person. There is simply too much information to be processed, and too much knowledge needed, to be within the capability of single individuals. As a result, decision making in modern organisations is now based on group discussions, meetings, and presentations, all to allow the exchange of a variety of perspectives from appropriately qualified people.

The next fact that we must accept is that such gatherings are often affected by ‘groupthink’. This is when tightly-knit cohorts of workers uncritically accept the feelings of the group (rather than ‘lighting it out’). Individual dissent is squashed, leaving decision-making not as a product of a pool of thinking individuals, all with valuable insights, but merely a collective desire to promote harmony. Clearly, this is not a method likely to optimise the chances of making the best decision.

So, two facts, which when brought together lead to the interesting conclusion: that some degree of conflict is necessary in order to produce better decision-making and, ultimately, higher organisational performance. Extending this further, somewhat paradoxically, very low levels or an absence of conflict may actually be worrying, indicating a lack of staff involvement or interest, or that problems are being hidden, new ideas stifled, and morale low. The focus thus shifts to conflict management (reducing conflict or creating it, as deemed optimum for the organisation), not conflict removal.

So, this is the contradiction. Change must happen, causing significant resistance and conflict, some of which is constructive and necessary, but some of which impedes progress. These feelings can originate from even the most level-headed, open-minded, and rational of people; thus, the next issue is how change agents can deal with it. One essential strategy is to listen to all those involved, even the angriest, most strident and difficult (since, after all, they may be right). Another strategy is to concur with what is factually accurate. People find it difficult to argue with those who agree with them, and this means resistance is reduced, communication enhanced, and insights into the situation will certainly come.

The third strategy for change agents is to always remind themselves of two basic facts. The first is not to expect complete rationality from those around them at all times. Expecting such ideal behaviour is itself irrational, and by resigning oneself to the inevitability of human failings, conflict can become more manageable. The other basic fact is that human beliefs are not necessarily encapsulations of the truth. Instead, they are often constructions of the mind, serving to maximise the security of the self. Thus, when encountering difficulties in implementing change, there is a good chance that the stakeholders are merely protecting such beliefs, and this should also be taken into account.

The experienced change agent realises that everyone’s perspective needs to he examined with an open mind. Conflicting viewpoints should be promoted in a healthy way, where people are disarmed and not reacting as a result of ill-feeling or malice. Yet. when such emotions emerge, the important point is to understand that it is not unnatural, and by understanding where it comes from and how to handle it. one can follow- constructive, rather than destructive, paths. It is not easy, but it is certainly possible.

Questions 27-30

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C, or D.

27. Organisations

A should be broken into divisions.

B need stable structures.

C are similar to living things.

D must be responsible.

28. Conflict

A is sometimes welcome.

B is usually good.

C should be removed.

D comes and goes.

29. Groupthink can

A be better than fighting.

B produce valuable insights.

C lead to wrong decisions.

D optimise chances.

30. Very little conflict is often

A better for organisations.

B good for morale.

C constructive.

D a warning sign.

Questions 31-35

Complete the flow chart. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

Questions 36-40

Answer the questions. Choose NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage for each answer.

36. What can even rational people still produce?

37. What sort of information should a change agent agree with?

38. What quality does not constantly come from people?

39. People often lie to enhance what feeling?

40. What emotions can produce unhealthy conflict?

ANSWER