Sentences in the English language come in a variety of forms and sizes, and it’s important for you to have a firm grasp of the different sentence patterns so that they may enhance the correctness and clarity of their own writing.

Whether using basic, compound, complex, or compound-complex sentences, a piece of writing with a diversity of sentence structures should be more dynamic and fascinating to read – and, as a result, should obtain a higher score.

As a result, this article will present the two basic sentence forms, simple and compound sentences, out of the four primary varieties.

However, before diving into particular sentence patterns, it’s critical to analyze the main aspects of a sentence so that we can effectively break any phrase down into its most relevant components.

What is a Sentence?

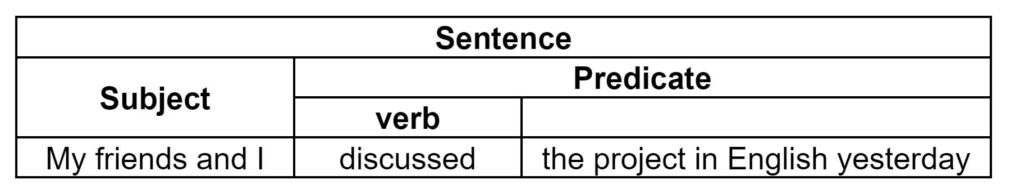

In simple terms, a sentence is a group of words with a complete thought, either direct or implied. The standard structure contains:

- subject – what is being talked about

- predicate – adds more details to the subject

A predicate and a subject are required in every phrase; a predicate contains a verb which is an action, and a subject is a noun that performs the action.

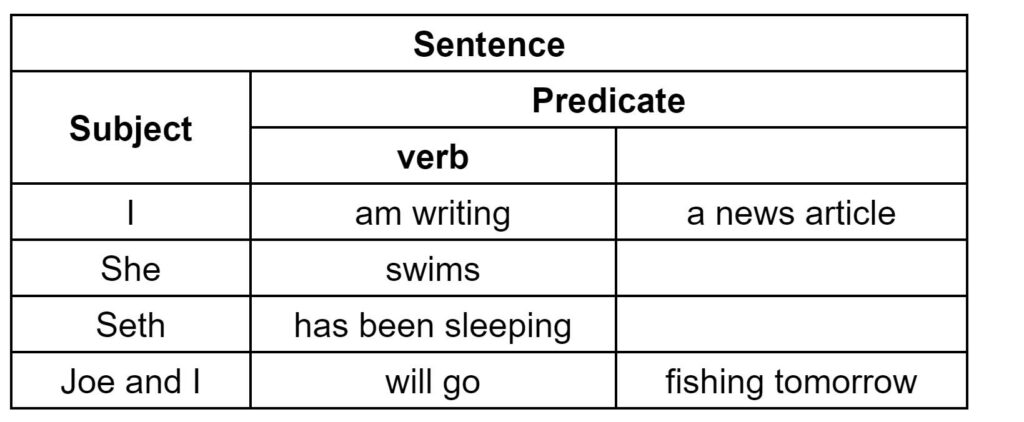

The verb in this phrase is ‘am writing.’ The base form of the verb is writing, but in the present continuous, we conjugate it with the –ing form and the auxiliary word am. While the subject or the doer of the action is “I.”

The sample sentence above is quite brief. Of course, a sentence might be lengthier and more sophisticated, but a subject and a predicate are always there. Take a look at this more detailed example:

It’s worth noting that the predicate is always followed by a verb. In certain cases, the predicate is just a verb:

As a result, we may argue that a sentence must have both a subject and a verb.

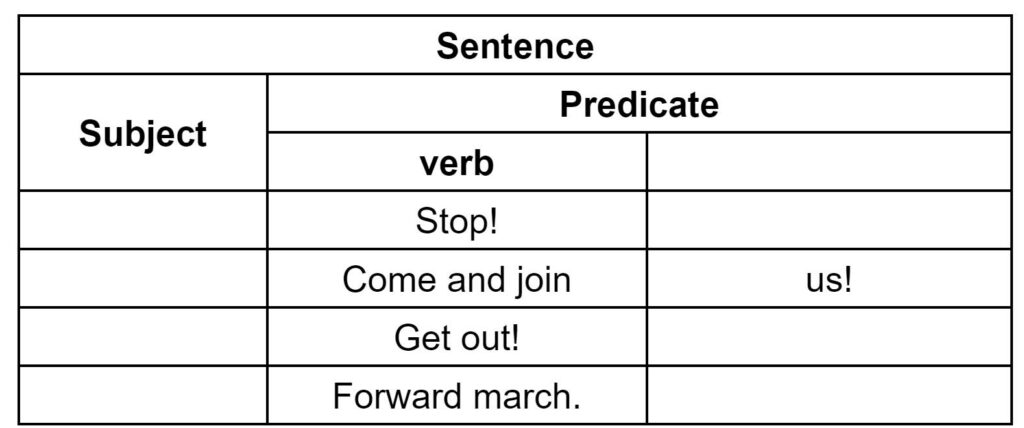

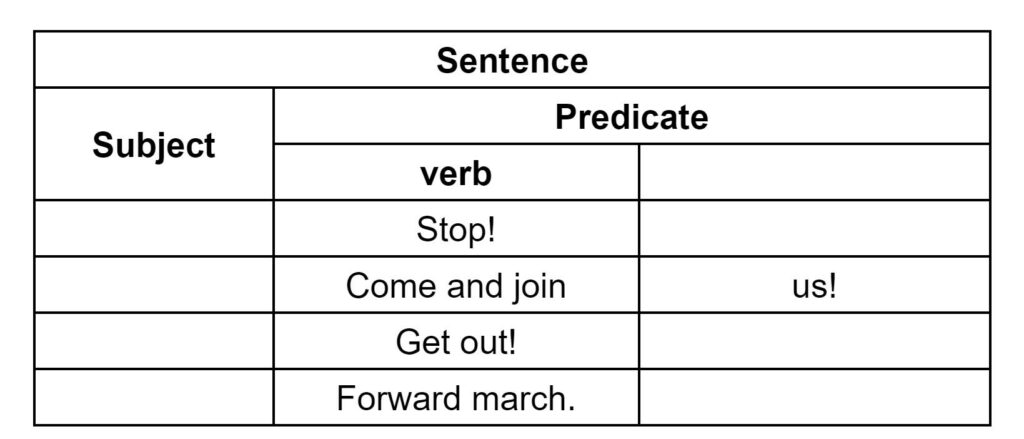

The imperative, however, seems to be an exception. When giving an order (the imperative), most people do not utilize a subject. They don’t state what the topic is because it’s self-evident: it’s YOU! Consider the following imperative examples, both with and without a subject:

Because both of the preceding statements, ‘I rested’ and ‘My ice cream has melted,’ include both subjects and verbs, they create grammatical sentences despite their small length. Sentences may be considerably longer in reality, and they can be made longer by adding objects, complements, and adverbials.

Why are Sentence Structures Important?

Reason #1: Thorough Editing

The first way that knowing sentence structures confidently will help your academic performance is that it will make you a better editor. While certain grammatical faults may be overlooked by a reader because they have little impact on meaning, this is not the case with problems in sentence structure.

Consider the following sample paragraph to show how such mistakes might alter meaning in context:

Clearly, when sentence structures are written wrongly, as in the example above, the meaning of such phrases may become quite difficult to understand. When reading the same text after making the appropriate modifications and edits, see whether you can see a difference in incoherence and clarity.

Many frequent sentence construction problems, such as phrase fragments, comma splices, and sentence run-ons, may all be avoided with a better understanding of this area of grammar. As a result, a student with this understanding and a good editor’s eye should be able to write better academic writing.

Reason #2: Active Writing

Another reason to study sentence structure is to make your writing more interesting and livelier. Examine the two paragraphs below. The first paragraph has nine brief sentences, most of which have just one subject and one verb. Contrast this with the second paragraph, which just has four phrases and communicates the same meaning:

Varying your sentence structure, just like in paragraph (2), is not just making your writing more dynamic than paragraph (1) but also simpler and more enjoyable to read since it employs a diversity of language styles. Your writing should become more dynamic and diverse as well, assuming you comprehend and can employ a range of sentence forms.

What are the Different Types of Sentence Structure?

It’s possible to categorize sentences into four different categories. Previously, we looked at the minimal prerequisites for constructing a sentence. We may now examine the four different forms of sentence construction in further depth.

| Simple | Compound | Complex | Compound-Complex |

|---|---|---|---|

| “She likes reading books.” | “She likes reading thriller novels, and her brother loves listening to classical music.” | “While her brother loves listening to classical music, she is more interested in thriller novels.” | “While her brother loves listening to classical music, she is more interested in thriller novels, and she prefers to be in a serene place.” |

Simple Sentences

Following that, we’ll look at a simple sentence like I love scuba diving.’ This kind of sentence is as simple to learn and recognize as it sounds and is one of the first structures that each English student will practice making. You just need to memorize the following four guidelines to write basic phrases correctly.

One Subject and One Verb

Subjects and verbs are required in practically all clauses (and hence all sentence constructions. The easiest way to figure out how many clauses are in a sentence is to count the number of subjects and major verbs. Fortunately, since simple sentences only need one clause, this is a fast and straightforward task. To demonstrate, each of the following phrases is basic since it only has one subject and one major verb:

One Independent Clause

As previously stated earlier, sentences may be made up of one or more clauses, and clauses can be independent or dependent.

Simple sentences, on the other hand, usually include a single independent clause with a single subject and one major verb. Below are both independent clauses since they may stand alone as entire ideas and phrases:

In other terms, a sentence’s structure is simple if it consists of just one independent phrase.

Additional Functional Phrases

A simple sentence, like the three examples in the table, can include objects, complements, and adverbials in addition to the subject and verb. It’s important to remember that a simple sentence can have a lot of objects, adverbials, and complements, but it always has one subject and one verb phrase:

| Subject | Verb | Object | Complement | Adverbials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | am writing | an article. | ||

| She | dances | gracefully | ||

| Seth | dove | into the pool |

Be mindful of compounded subjects/verbs

While we previously examined how simple sentences (and clauses in general) only have one subject, it is possible for such clauses to seem to have two subjects.

| Subject | Predicate |

|---|---|

| “Moises and Joyce” | “am writing a news article” |

Although these sentences seem to contain two subjects – ‘Moises’ and ‘Joyce’ – which have been united by the coordinate conjunction ‘and,’ these two subjects really constitute the single subject ‘we,’ as in ‘We are writing a news article.’ Even though there are two parts that seem to be independent topics, this sentence is nevertheless deemed simple in structure.

Compound Sentences

Compound sentences, on the other hand, must have two distinct subjects to be grammatical — however, these subjects should be spread out across two separate clauses rather than one.

Since compound sentences are one of the most popular of the four sentence forms, you must know how to utilize and recognize this sentence type correctly – especially in academic writing. The following four principles, similar to simple sentences, should always be observed if you want to utilize compound sentences appropriately in your written work.

Use Independent Clause Only

Compound sentences, like simple sentences, are made up of just separate clauses with both subject and predication and can stand on its own as full ideas and phrases. The employment of coordinating conjunctions like ‘and’ or ‘but’ to unite these clauses is one evident evidence of a compound phrase. If the phrase in issue, on the other hand, includes subordinating conjunction like ‘because’ or ‘even though,’ it is a dependent clause and not a compounded construction.

Use Can Use Multiple Independent Clauses

Compound sentences, unlike simple sentences, must include two or more separate clauses to be termed compound. To show compound structures with two or more separate clauses, consider the following examples:

Examples:

- “We were told to work on these pages, yet I am still confused about the task.”

- “I am confident and know I can make it to the finish line, but I am a bit worried.”

The compound sentence in:

- contains two separate clauses united by a comma (,) and the coordinate conjunction ‘and,’ while the compound phrase in

- has three independent clauses joined by commas and the conjunctions ‘but’ and ‘and.’

There is no grammatical limit to how many independent clauses may be combined in this manner in compound phrases like these; but more than three separate clauses in one sentence becomes difficult for readers to follow.

Structure Compound Sentences Correctly

When constructing compound sentences, you must learn to combine their independent clauses appropriately; otherwise, they may end up with ungrammatical run-on sentences, comma splices, and sentence fragments.

As seen in the preceding instances, the basic and most generally used rule is that every independent phrase should be coupled with a comma (,) and a coordinating conjunction (and, so, but, etc.).

When the writer wants to establish a stronger relationship between two independent clauses, he or she might use a semi-colon (;), which is likewise fully valid in compound sentences:

- “We had a meeting; we did not resolve anything.”

- “I am working on the project; I am not sure when it can be done.”

What isn’t grammatically correct is linking two distinct sentences with simply a comma, since this results in an ungrammatical comma splice, which is a sort of phrase run-on:

“We had a meeting, we did not resolve anything.”

“I am working on project, I am not sure when it can be done.”

A comma splice is when two distinct clauses are joined with a comma and no conjunction. Some people view this as a run-on phrase, while others see it as a punctuation mistake.

Compounding, in General, Should Be Avoided.

Finally, make sure that you don’t get mixed up between the general compounding of sentence parts like noun phrases and the merging of two or more separate clauses. Because both structures employ coordinating conjunctions like ‘and’ to unite their elements, such misunderstanding is likely to arise. As seen in the instances below, poor identification of these structures may lead you to employ inappropriate punctuation or conjunctions, resulting in grammatical structures:

Examples:

- “I am learning French and Spanish languages, and I am practicing everyday.”

In example (i), a comma (,) has been used to divide the two nouns ‘French’ and ‘Spanish,’ although the comma should be put before the second ‘and’ conjunction, not the first. This is because the second conjunction marks combining the two separate clauses that make up the grammatical compound phrase in the first place (i).

Complex Sentences

While simple and compound sentences are helpful while writing academically, you’ll also need to employ a range of complicated sentence forms to make your writing more dynamic and interesting. We will give three guidelines that you should grasp and follow attentively to help you recognize and use complicated phrases.

Have a Combination Independent with Dependent Clauses

Unlike simple and compound sentences, complex sentences need both an independent clause and a dependent clause to be deemed grammatical, as seen in the examples below. The independent clauses have been highlighted in both of these sentences:

- “He struggled badly with his exams because he did not study last night.”

- “Since he did not study last night, he struggled badly with his exams.”

Because (1) all sentence structures require at least one independent clause, and (2) these clauses have been joined with the bolded subordinate conjunctions because’ and ‘since,’ we can tell that these two example complex sentences are made up of a mixture of independent and dependent clauses. Subordinating conjunctions like these are often employed to introduce dependent clauses, which aren’t entire ideas or sentences on their own.

Expect to See a Wide Range of Dependent Clauses

While it may seem that the independent and dependent clauses in the preceding instances may be easily distinguished, there is such a wide range of dependent clause forms that this isn’t always the case.

In general, dependent clauses can join independent clauses with relative pronouns like ‘who‘ or ‘which,’ they can show the time or sequence of a clause with subordinate conjunctions like ‘since‘ or ‘while,’ and they can show the causal relationship between clauses with conjunctions like ‘because’ and ‘if.’ To aid in recognition of such sentence patterns, the four-alternative dependent-clause forms have been highlighted in bold below.

Various Kinds of Dependent Clause

| Adjective Clauses | We love the teacher who teaches our English subject. |

| Adverbial Clauses | Unless you pass the exam, you will surely fail the subject. |

| Noun Clauses | Are you aware of why we are here? |

| Non-finite Clauses | Nadia went to the village to visit her family. |

Notice how the dependent clause in the non-finite clause example ‘to visit her family’ appears to breach the first requirement of being a clause in that it lacks both a subject and a verb, instead of relying only on the word ‘visit.’ This is due to the fact that in non-finite clauses, the subject (in this example, ‘Nadia’) is deemed to be included inside the superordinating independent clause.

Correctly Punctuate Complex Sentences

Finally, you’ve undoubtedly noticed several differences in the punctuation and sequence of the preceding sample difficult phrases. It’s worth noting that, especially with adverbial clauses, the dependent or independent clause might be positioned either at the start or end of a sentence, depending on the writer’s preference:

| Dependent Clause | Independent Clause |

|---|---|

| “Since the Covid-19 cases are rising, students are still attending online classes.” | “Students are still attending online classes since the Covid-19 cases are rising.“ |

| “Although the majority of Indonesians are vaccinated, the government continuously reminds the population to be careful.” | “The government continuously reminds the population to be careful, although the majority of Indonesians are vaccinated.“ |

When putting the dependent clause first, however, writers must always include a comma (,) between the dependent and independent clauses to properly link them. When the independent phrase is at the beginning of the complicated sentence, however, a comma is not required – in fact, including one would be grammatically incorrect.

Compound-Complex Sentences

Compound-complex sentences, as the name implies, are the hardest to comprehend.

Longer, more difficult concepts may be expressed using compound-complex sentences, which have more elements than normal phrases. They’re useful for presenting complex concepts or detailing extensive sequences of occurrences.

Writers may simply generate a compound-complex sentence structure by combining compound and complex sentences, which will have at least two independent clauses and one dependent clause. In principle, a compound-complex sentence may be as long as it wants to be, but in fact, excessively long phrases might be difficult to understand.

The following compound-complex statement with eleven clauses, for example, is entirely grammatical despite its awkwardness:

The professor stepped onto the stage1 to make his guest appearance2, despite the fact that he wasn’t prepared3 to make a speech or deliver this lecture4, which he’d spent barely five minutes rehearsing5, to the audience of peers and students6 who sat eagerly awaiting the first word7 that would soon leave his mouth8, given confidence by years of experience9 and energized by the anticipatory crowd10.

| Adjective Clauses | 5, 7, 8, 9, 10 |

| Adverbial Clauses | 3 |

| Noun Clauses | 1 |

| Non-finite Clauses | 2, 4, 6 |

Sentence Run-Ons and Fragments

Now that you should be able to recognize and employ basic, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentence structures in your own writing, we should look at the sorts of errors that you tend to make while writing sentences. A run-on (or fused) phrase is the first major type of error.

When two whole phrases are mashed together without a coordinating conjunction or suitable punctuation, such as a period or a semicolon, run-on sentences are also known as run-on sentences.

Short or extended run-on phrases are acceptable. A lengthy phrase isn’t always synonymous with a run-on sentence.

Why Should Sentence Run-ons Be Avoided in English for Academic Purposes (EAP)?

Below are examples of run-on sentences made up of two separate clauses. It combines two entire ideas into a single statement with no punctuation:

| Incorrect | Correct |

|---|---|

| “Even though Lila prefers roses John gives her a bouquet of tulips instead.” | “Even though Lila prefers roses, John gives her a bouquet of tulips instead.” |

| “Lila liked the tulip bouquet John gave her on prom night, she loves roses.” | “Lila liked the tulip bouquet John gave her on prom night; however, she loves roses.” |

In example (a), the dependent clause ‘even though Lila prefers roses’ has been attached to the independent clause following it without the use of a comma (,), resulting in a complicated ungrammatical phrase.

Similarly, in example (b), two separate clauses have been joined into a compound phrase with just one comma, resulting in a comma splice. This method of joining two separate clauses is ungrammatical and should be avoided by you at all costs.

Thankfully, as the examples below show, two straightforward solutions exist to correct each statement.

In example (a), we can simply add a comma or reverse the order of the dependent and independent clauses, however in example (b), we may add coordinate conjunction or replace the comma with a semicolon (;).

When employing compound-complex sentences, things become a little more challenging since these structures may be virtually any length and yet be correct (although overly long sentences are admittedly difficult to understand).

It is consequently not the length of a phrase that determines whether it is regarded as a run-on but rather the presence or absence of improper or missing conjunctions and punctuation.

With this in mind, there are three common methods for students to construct sentence run-ons rather than correct sentences, and students should learn to avoid each:

Connecting Two Independent Clauses + Conjunctive Adverb

| Incorrect | “The flight was delayed for an hour, nevertheless, the passengers did not mind.” |

| Correct | “The flight was delayed for an hour; nevertheless, the passengers did not mind.” |

| Correct | “The flight was delayed for an hour. Nevertheless, the passengers did not mind.” |

Using a Pronoun Antecedent in the Second Independent Clause

| Incorrect | “The Angat Dam was heavily damaged, it was not built properly.” |

| Correct | “The Angat Dam was heavily damaged because it was not built properly.” |

| Correct | “The Angat Dam was heavily damaged; it was not built properly.” |

Adding a command as a Second Independent Clause

| Incorrect | “We might have unfavorable weather, bring an umbrella.” |

| Correct | “We might have unfavorable weather, so bring an umbrella.” |

| Correct | “We might have unfavorable weather. Bring an umbrella.” |

When conjunctive adverbs like ‘although’ and ‘therefore’ are used to connect two separate clauses in scenario 1, a semicolon (;) should come before the adverb, and a comma (,) should come after it. Scenarios 2 and 3 are, however, somewhat different.

Both of these examples include comma splices, which occur when a comma is used wrongly to combine two separate clauses – a typical mistake.

Thankfully, using the correct conjunction and/or punctuation mark may typically correct such problems quickly.

What are the Grammar Rules for Creating Various Sentence Structures?

You must also obey the grammatical rules in addition to understanding the elements of a phrase.

Here’s a short rundown in case you forgot:

- In a sentence, capitalize the initial letter of the first word.

- Use a period, a question mark, an exclamation point, or quote marks to end a phrase.

- The subject of the sentence usually appears first, followed by the verb, and then the objects. (Subject -> Verb -> Object)

- If the subject is single, the verb must be singular as well. Subject-verb agreement occurs when the verb must be plural if the subject is plural.

Are Sentence Structures Challenging for Students?

When it comes to sentence building, it’s not just about grammar; it’s also about style and flow. A range of sentence lengths and styles are used in effective academic writing. Overly lengthy sentences might be confusing to readers, while too many extremely short sentences can make your content seem jagged and fragmented.

Don’t Use Run-on Phrases.

An independent clause is has a complete thought and that may stand alone. Independent clauses may be combined in a variety of ways, but when they are joined without adequate punctuation, a run-on phrase results.

Run-on sentences are a grammatical issue, not a long one; even short phrases may include this problem. Run-on phrases are the consequence of two typical errors.

| Incorrect | Correct | |

| Comma Splice | “Nadia loves to take cream and sugar with her tea, when she drinks it warm, she also likes it black.” | “Nadia loves to take cream and sugar with her tea; when she drinks it warm, she also likes it black.” |

Sentence Fragments Should be Avoided.

Remember that fragments are groups of words that lack all of the elements of a complete sentence. A sentence must contain a subject and a predicate to be considered complete.

Sentence fragments are frequently used stylishly in journalism and creative writing but are seldom acceptable in academic or other formal writing.

| Incorrect | Correct | |

| Missing subject or predicate | “The newspaper article today” | “The newspaper article today is very controversial.” |

| Very controversial | ||

| A dependent clause | “When the sky is clear” | “The sky is clear.” |

Overly Long Sentences Should Be Broken Up.

A lengthy sentence may be grammatically accurate, yet it is difficult to follow due to its length. Avoid using too many overly long sentences in your writing to make it clearer and more readable.

Take note that a typical sentence is usually 15 to 25 words long. If your sentence becomes longer than 30-40 words, you should consider revising it. Getting rid of redundancies and inflated phrases is a good place to start, but if all of the words in a sentence are necessary, try breaking it up into smaller sentences.

| Incorrect | Correct |

| “While numerous previous studies have shown that there are 80% of Filipinos are willing to get a Covid booster, our data show that the percentage of people who refuse to obtain a booster dosage varies little by region, ranging from 6-7 percent.” | “While numerous previous studies have shown that there are 80% of Filipinos are willing to get a Covid booster.Our data, however, show that the percentage of people who refuse to obtain a booster dosage varies little by region, ranging from 6-7 percent.” |

Join Sentences that are Too Short Together.

Shorter sentences are usually cleaner and easier to read, but too many of them may make writing appear jagged, fragmented, or repetitious. Use transition words and a range of sentence lengths to let readers understand how your thoughts fit together.

| Incorrect | “San Francisco is one of my beloved cities to live in. I live in a beautiful apartment. It provides a spectacular perspective of the whole city. Underneath, I can see the Golden Gate Bridge. Every day, a great number of ships pass through. San Francisco is also a favorite of mine. I can discover fantastic restaurants that serve cuisine from almost every nation. The city’s traffic irritates me.” |

| Correct | “San Francisco is one of my beloved cities to live in, and I live in a beautiful apartment. In addition, it provides a spectacular perspective of the whole city. Underneath, I can see the Golden Gate Bridge. Every day, a great number of ships pass through. San Francisco is also a favorite of mine, where I can discover fantastic restaurants that serve cuisine from almost every nation; however, the city’s traffic irritates me.” |

7 Best Tips in Varying your Sentences

The necessity to alter your syntax and written rhythms to keep your reader interested is a crucial part of the writing process. Word choice, tone, vocabulary, and, perhaps most importantly, sentence structure are all examples of diversity.

When reading a book, news story, or magazine article, readers strive for sentence diversity, even if they aren’t aware of it. No matter what writing style you use, one of the finest writing advice a first-time author can get is to use a variety of sentence structures.

Here are some writing strategies to help you add diversity to your sentences.

Enjoying brevity

If your first statement is complex, keep your second sentence brief and straightforward. Shorter phrases with no unclear words are strong. The reader is engaged when you write with clarity and conciseness.

Simple Sentences After Lengthy Phrases

A thick sentence is one with at least two independent clauses and one dependent clause. Simplifying statements are excellent, but repeating them may be boring. If you compose one, use a different sentence type.

Avoid Using Passive Voices.

Active voice verbs describe the action. “He caught the ball.” This sentence conveys the same information in a less pleasant manner. A passive statement might adequately describe a situation, but you should usually employ the active voice.

Use a Mix of Transitions.

“However,” “therefore,” “moreover,” and other conjunctive adverbs may be used as transition words. These terms are excellent as long as you don’t use pet phrases.

Using Semicolons Reduces Conjunctions.

A compound sentence joins two separate clauses with a coordinating conjunction. To add variety to your sentences, use a semicolon after the first independent clause. But you’ve introduced variation to your sentence patterns.

Start Paragraphs with a Concise Thesis Statement.

A thesis statement is a straightforward and declarative phrase. Generally, longer sentences are preferable to shorter ones. In the body of your paragraphs, elaborate on these claims.

Use Rhetoric.

Rhetorical questions are assertions posed as questions to arouse curiosity. “What if there was no war?” These lines work well in both creative and content writing. Use them wisely.