READING PASSAGE 1

Airports on Water

River deltas are difficult places for map makers. The river builds them up, the sea wears them down; their outlines are always changing. The changes in China’s Pearl River delta, however, are more dramatic than these natural fluctuations. An island six kilometres long and with a total area of 1248 hectares is being created there. And the civil engineers are as interested in performance as in speed and size. This is a bit of the delta that they want to endure.

The new island of Chek Lap Kok, the site of Hong Kong’s new airport, is 83% complete. The giant dumper trucks rumbling across it will have finished their job by the middle of this year and the airport itself will be built at a similarly breakneck pace.

As Chek Lap Kok rises, however, another new Asian island is sinking back into the sea. This is a 520-hectare island built in Osaka Bay, Japan, that serves as the platform for the new Kansai airport. Chek Lap Kok was built in a different way, and thus hopes to avoid the same sinking fate.

The usual way to reclaim land is to pile sand rock on to the seabed. When the seabed oozes with mud, this is rather like placing a textbook on a wet sponge: the weight squeezes the water out, causing both water and sponge to settle lower. The settlement is rarely even: different parts sink at different rates. So buildings, pipes, roads and so on tend to buckle and crack. You can engineer around these problems, or you can engineer them out. Kansai took the first approach; Chek Lap Kok is taking the second.

The differences are both political and geological. Kansai was supposed to be built just one kilometre offshore, where the seabed is quite solid. Fishermen protested, and the site was shifted a further five kilometres. That put it in deeper water (around 20 metres) and above a seabed that consisted of 20 metres of soft alluvial silt and mud deposits. Worse, below it was a not-very- firm glacial deposit hundreds of metres thick.

The Kansai builders recognised that settlement was inevitable. Sand was driven into the seabed to strengthen it before the landfill was piled on top, in an attempt to slow the process; but this has not been as effective as had been hoped. To cope with settlement, Kansai’s giant terminal is supported on 900 pillars. Each of them can be individually jacked up, allowing wedges to be added underneath. That is meant to keep the building level. But it could be a tricky task.

Conditions are different at Chek Lap Kok. There was some land there to begin with, the original little island of Chek Lap Kok and a smaller outcrop called Lam Chau. Between them, these two outcrops of hard, weathered granite make up a quarter of the new island’s surface area. Unfortunately, between the islands there was a layer of soft mud, 27 metres thick in places.

According to Frans Uiterwijk, a Dutchman who is the project’s reclamation director, it would have been possible to leave this mud below the reclaimed land, and to deal with the resulting settlement by the Kansai method. But the consortium that won the contract for the island opted opted for a more aggressive approach It scrambled the world’s largest lot of dredgers, which sucked up 150m cubic metres of clay mud and dumped it in deeper waters. At the same time sand was dredged from the waters and piled on top of the layer of stiff clay that the massive dredging had laid bare.

Nor was the sand the only thing used. The original granite island which had hills up to 120 metres high was drilled and blasted into boulders no bigger than two metres in diameter. This provided 70m cubic metres of granite to add to the island’s foundations. Because the heap of boulders does not fill the space perfectly, this represents the equivalent of 105m cubic metres of landfill. Most of the rock will become the foundations for the airport’s runways and its taxiways. The sand dredged from the waters will also be used to provide a two-metre capping layer over the granite platform. This makes it easier for utilities to dig trenches – granite is unyielding stuff. Most of the terminal buildings will be placed above the site of the existing island. Only a limited amount of pile-driving is needed to support building foundations above softer areas.

The completed island will be six to seven metres above sea level. In all, 350m cubic metres of material will have been moved. And much of it, like the overloads, has to be moved several times before reaching its final resting place. For example, there has to be a motorway capable of carrying 150-tonne dump-trucks; and there has to be a raised area for the 15,000 construction workers. These are temporary; they will be removed when the airport is finished.

The airport, though, is here to stay. To protect it, the new coastline is being bolstered with a formidable twelve kilometres of sea defences. The brunt of a typhoon will be deflected by the neighbouring island of Lantau; the sea walls should guard against the rest. Gentler but more persistent bad weather – the downpours of the summer monsoon – is also being taken into account. A mat-like material called geotextile is being laid across the island to separate the rock and sand layers. That will stop sand particles from being washed into the rock voids, and so causing further settlement. This island is being built never to be sunk.

Questions 1-5

Classify the following statements as applying to

A Chek Lap Kok airport only

B Kansai airport only

C Both airports

1 having an area of over 1000 hectares

2 built in a river delta

3 built in the open sea

4 built by reclaiming land

5 built using conventional methods of reclamation

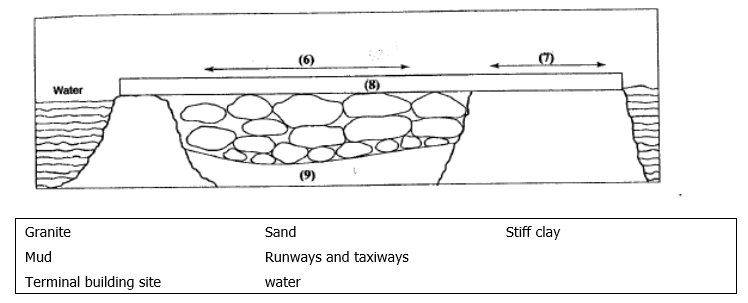

Questions 6-9

Complete the labels on Diagram below. Choose your answers from the box below the diagram and write them in boxes 6-9 on your answer sheet.

READING PASSAGE 2

Changing our Understanding of Health

A The concept of health holds different meanings for different people and groups. These meanings of health have also changed over time. This change is no more evident than in Western society today, when notions of health and health promotion are being challenged and expanded in new ways.

B For much of recent Western history, health has been viewed in the physical sense only. That is, good health has been connected to the smooth mechanical operation of the body, while ill health has been attributed to a breakdown in this machine. Health in this sense has been defined as the absence of disease or illness and is seen in medical terms. According to this view, creating health for people means providing medical care to treat or prevent disease and illness. During this period, there was an emphasis on providing clean water, improved sanitation and housing.

C In the late 1940s the World Health Organisation challenged this physically and medically oriented view of health. They stated that ‘health is a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being and is not merely the absence of disease’ (WHO, 1946). Health and the person were seen more holistically (mind/body/spirit) and not just in physical terms.

D The 1970s was a time of focusing on the prevention of disease and illness by emphasizing the importance of the lifestyle and behaviour of the individual. Specific behaviours which were seen to increase risk of disease, such as smoking, lack of fitness and unhealthy eating habits, were targeted. Creating health meant providing not only medical health care, but health promotion programs and policies which would help people maintain healthy behaviours and lifestyles. While this individualistic healthy lifestyles approach to health worked for some (the wealthy members of society), people experiencing poverty, unemployment, underemployment or little control over the conditions of their daily lives benefited little from this approach.

This was largely because both the healthy lifestyles approach and the medical approach to health largely ignored the social and environmental conditions affecting the health of people.

E During the 1980s and 1990s there has been a growing swing away from lifestyle risks as the root cause of poor health. While lifestyle factors still remain important, health is being viewed also in terms of the social, economic environmental contexts in which people live. This broad approach to health is called the socio-ecological view of health. The broad socio-ecological view of health was endorsed at the first International Conference of Health Promotion held in 1986, Ottawa, Canada, where people from 38 countries agreed and declared that:

The fundamental conditions and resources for health are peace, shelter, education, food, a viable income, a stable eco-system, sustainable resources, social justice and equity. Improvement in health requires a secure foundation in these basic requirements. (WHO, 1986)

It is clear from this statement that the creation of health is about much more than encouraging healthy individual behaviours and lifestyles and providing appropriate medical care. Therefore, the creation of health must include addressing issues such as poverty, pollution, urbanisation, natural resource depletion, social alienation and poor working conditions. The social, economic and environmental contexts which contribute to the creation of health do not operate separately or independently of each other. Rather, they are interacting and interdependent, and it is the complex interrelationships between them which determine the conditions that promote health. A broad socio-ecological view of health suggests that the promotion of health must include a strong social, economic and environmental focus.

F At the Ottawa Conference in 1986, a charter was developed which outlined new directions for health promotion based on the socio-ecological view of health. This charter, known as the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, remains as the backbone of health action today. In exploring the scope of health promotion it states that:

Good health is a major resource for social, economic and personal development and an important dimension of quality of life. Political, economic, social, cultural, environmental, behavioural and biological factors can all favour health or be harmful to it. (WHO, 1986)

The Ottawa Charter brings practical meaning and action to this broad notion of health promotion. It presents fundamental strategies and approaches in achieving health for all. The overall philosophy of health promotion which guides these fundamental strategies and approaches is one of ‘enabling people to increase control over and to improve their health’ (WHO, 1986).

Questions 14-18

Reading passage 2 has six paragraphs A-F. Choose the most suitable headings for paragraphs B-F from the list of headings below. Write the appropriate numbers (i-ix) in boxed 14-18 on your answer sheet.

NB There are more headings than paragraphs so you will not use them all.

List of Headings

i. Ottawa International Conference on Health Promotion

ii. Holistic approach to health

iii. The primary importance of environmental factors

iv. Healthy lifestyles approach to health

v. Changes in concepts of health in Western society

vi. Prevention of diseases and illness

vii. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion

viii. Definition of health in medical terms

ix. Socio-ecological view of health

14 Paragraph B

15 Paragraph C

16 Paragraph D

17 Paragraph E

18 Paragraph F

Questions 19-22

Using NO MORE THAN THREE WORDS from the passage answer the following questions.

19 In which year did the World Health Organisation define health in terms of mental, physical and social well-being?

20 Which members of society benefited most from the healthy lifestyles approach to health?

21 Name the three broad areas which relate to people’s health, according to the socio-ecological view of health.

22 During which decade were lifestyle risks seen as the major contributors to poor health?

Questions 23-27

Do the following statements agree with the information in Reading Passage 2?

YES if the statement agrees with the information

NO if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this in the passage

23 Doctors have been instrumental in improving living standards in Western society.

24 The approach to health during the 1970s included the introduction of health awareness programs.

25 The socio-ecological view of health recognises that lifestyle habits and the provision of adequate health care are critical factors governing health.

26 The principles of the Ottawa Charter are considered to be out of date in the 1990s.

27 In recent years a number of additional countries have subscribed to the Ottawa Charter.

READING PASSAGE 3

Children’s Thinking

One of the most eminent of psychologists, Clark Hull, claimed that the essence of reasoning lies in the putting together of two ‘behaviour segments’ in some novel way, never actually performed before, so as to reach a goal.

Two followers of Clark Hull, Howard and Tracey Kendler, devised a test for children that was explicitly based on Clark Hull’s principles. The children were given the task of learning to operate a machine so as to get a toy. In order to succeed they had to go through a two-stage sequence. The children were trained on each stage separately. The stages consisted merely of pressing the correct one of two buttons to get a marble; and of inserting the marble into a small hole to release the toy.

The Kendlers found that the children could learn the separate bits readily enough. Given the task of getting a marble by pressing the button they could get the marble; given the task of getting a toy when a marble was handed to them, they could use the marble. (All they had to do was put it in a hole.) But they did not for the most part ‘integrate’, to use the Kendlers’ terminology. They did not press the button to get the marble and then proceed without further help to use the marble to get the toy. So the Kendlers concluded that they were incapable of deductive reasoning.

The mystery at first appears to deepen when we learn, from another psychologist, Michael Cole, and his colleagues, that adults in an African culture apparently cannot do the Kendlers’ task either. But it lessens, on the other hand, when we learn that a task was devised which was strictly analogous to the Kendlers’ one but much easier for the African males to handle.

Instead of the button-pressing machine, Cole used a locked box and two differently coloured match-boxes, one of which contained a key that would open the box. Notice that there are still two behaviour segments – ‘open the right match-box to get the key’ and ‘use the key to open the box’ – so the task seems formally to be the same. But psychologically it is quite different. Now the subject is dealing not with a strange machine but with familiar meaningful objects; and it is clear to him what he is meant to do. It then turns out that the difficulty of ‘integration’ is greatly reduced.

Recent work by Simon Hewson is of great interest here for it shows that, for young children, too, the difficulty lies not in the inferential processes which the task demands, but in certain perplexing features of the apparatus and the procedure. When these are changed in ways which do not at all affect the inferential nature of the problem, then five-year-old children solve the problem as well as college students did in the Kendlers’ own experiments.

Hewson made two crucial changes. First, he replaced the button-pressing mechanism in the side panels by drawers in these panels which the child could open and shut. This took away the mystery from the first stage of training. Then he helped the child to understand that there was no ‘magic’ about the specific marble which, during the second stage of training, the experimenter handed to him so that he could pop it in the hole and get the reward.

A child understands nothing, after all, about how a marble put into a hole can open a little door. How is he to know that any other marble of similar size will do just as well? Yet he must assume that if he is to solve the problem. Hewson made the functional equivalence of different marbles clear by playing a ‘swapping game’ with the children.

The two modifications together produced a jump in success rates from 30% to 90% for five year olds and from 35% to 72.5% for four year olds. For three year olds, for reasons that are still in need of clarification, no improvement – rather a slight drop in performance – resulted from the change.

We may conclude then, that children experience very real difficulty when faced with the Kendler apparatus, but this difficulty cannot be taken as proof that they are incapable of deductive reasoning.

Questions 28-35

Classify the following descriptions as referring to

CH Clark Hull

HTK Howard and Tracey Kendler

MC Michael Cole and colleagues

SH Simon Hewson

Write the appropriate letters in boxes 28-35 on your answer sheet. NB You may use any answer more than once.

28………….is cited as famous in the field of psychology.

29…………demonstrated that the two stage experiment involving button pressing and inserting a marble into a hole poses problems for certain adults as well as children.

30………..devised an experiment that investigated deductive reasoning without the use of any marbles.

31………..appears to have proved that a change in the apparatus dramatically improves the performance of children of certain ages.

32………..used a machine to measure inductive reasoning that replaced button pressing with drawer opening.

33………..experimented with things that the subjects might have been expected to encounter in everyday life, rather than with a machine.

34………..compared the performance of five year olds with college students using the same apparatus with both sets of subjects.

35………..is cited as having demonstrated that earlier experiments into children’s ability to reason deductively may have led to the wrong conclusions.

Questions 36-40

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 3? In boxes 36 40 on your answer sheet write

YES if the statement agrees with the information

NO if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no informal ion on this in the passage

36 Howard and Tracey Kendler studied under Clark Hull.

37 The Kendlers trained their subjects separately in the two stages of their experiment, but not in how to integrate the two actions.

38 Michael Cole and his colleagues demonstrated that adult performance on inductive reasoning tasks depends on features of the apparatus and procedure.

39 All Hewson’s experiments used marbles of the same size.

40 Hewson’s modifications resulted in a higher success rate for children of all ages.

ANSWER

1. A

2. A

3. B

4. C

5. B

6. runways and taxiways

7. terminal building site

8. sand

9. stiff clay

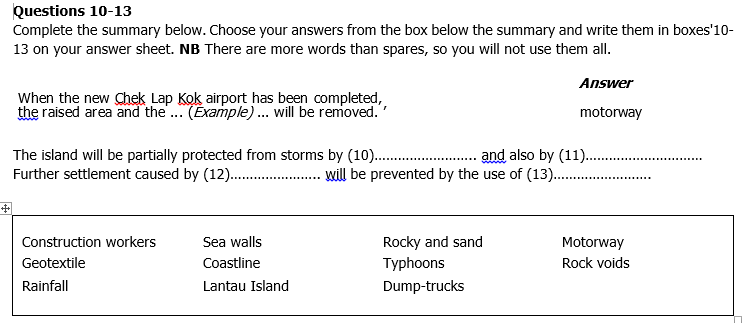

10. lantau island

11. sea walls

12. rainfall

13. geotextile

14. viii

15. ii

16. iv

17. ix

18. vii

19. 1946

20. wealthy of society

21. social, economic, environmental

22. 1970s

23. not given

24. yes

25. no

26. no

27. not given

28. CH

29. MC

30. MC

31. SH

32. SH

33. MC

34. HTK

35. SH

36. not given

37. yes

38. yes

39. not given

40. no